WhatsApp,

Facebook Inc.

’s popular messaging tool, had just notified about 1,400 users—among them the suspected terrorist—that their phones had been hacked by an “advanced cyber actor.” An elite surveillance team was using spyware from

NSO Group,

an Israeli company, to track the suspect, according to a law-enforcement official overseeing the investigation.

A judge in the Western European country had authorized investigators to deploy all means available to get into the suspect’s phone, for which the team used its government’s existing contract with NSO. The country’s use of NSO’s spyware wasn’t known to Facebook. NSO licenses its spyware to government clients, who use it to hack targets.

On Oct. 29, Facebook filed suit against NSO—which has been enmeshed in controversy after governments used its technology to spy on dissidents—in federal court in California, seeking unspecified financial penalties over NSO’s alleged hacking of WhatsApp software. It also sought an injunction prohibiting NSO from accessing Facebook and WhatsApp’s computer systems.

NSO said it is vigorously defending itself against the lawsuit, without elaborating.

Technology companies such as Facebook and

Apple Inc.

over recent years have strengthened the security of their systems to the point where even the tech companies themselves can’t provide law-enforcement agencies with messages created on their own systems.

Private companies, meanwhile, have stepped in to fill the gap by devising new ways of extracting data from computers and mobile devices. Facebook said in the lawsuit that spyware was installed by hacking WhatsApp’s video-calling function.

The thwarted terror investigation, as described by the law-enforcement official, spotlights an increasingly common clash of concerns over public security and personal privacy. Tech companies have come under growing pressure in the U.S. and Europe to give law enforcement a back door into encrypted messages. But they are also under fire for not doing enough to protect the privacy of their users and, in some jurisdictions, they have legal obligations to disclose security breaches.

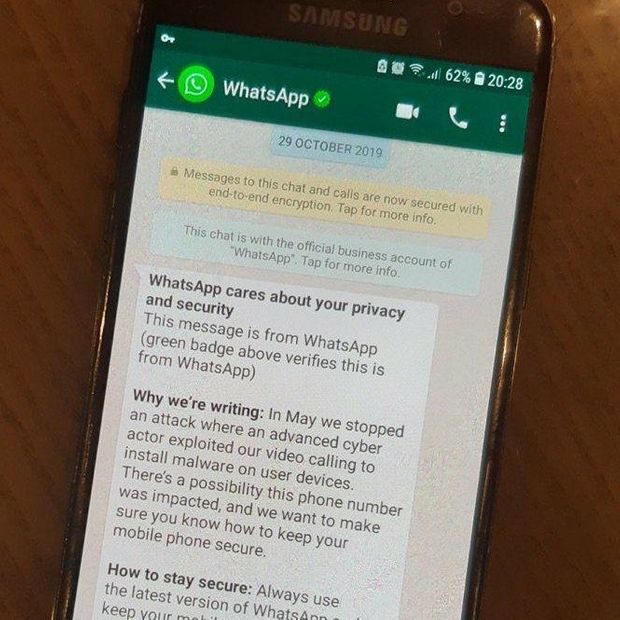

WhatsApp’s Oct. 29 message to users warned journalists, activists and government officials that their phones had been compromised, Facebook said. But it also had the unintended consequence of potentially jeopardizing multiple national-security investigations in Western Europe about which Facebook hadn’t been alerted—and about which government agencies can’t formally complain, given their secret nature.

“The hacking methods described in our lawsuit against the NSO Group are illegal. We remain committed to the security and protection of users from cyberattacks,” WhatsApp said.

Cracking the Code

Law enforcement in Western European nations turned to NSO Group to tap into terror suspects’ phones and prevent attacks.

To get access to these phones, law enforcement turns to NSO Group. Its software connects with the phone by spoofing legitimate WhatsApp communications. It exploits a bug in WhatsApp’s software to trick it into installing NSO software.

Law enforcement learns of terror suspect using WhatsApp’s encrypted messaging, which scrambles the content of messages. These messages are only readable on the phones of the sender and recipient.

1

2

Install!

NSO Group

With the NSO software now running on the target’s phone, the company’s customers have a powerful spying tool that can read messages, take screenshots, and download browser history and contact lists.

After identifying that journalists and activists have been targeted, on Oct. 29 Facebook sues NSO for hacking and notifies 1,400 targets that their phones may have been compromised. It doesn’t know the identity of most of these users.

3

4

Shortly after, the NSO software installed on these phones goes dark, either because the targets of investigations have reformatted their phones or discarded them.

5

Law enforcement learns of terror suspect using WhatsApp’s encrypted messaging, which scrambles the content of messages. These messages are only readable on the phones of the sender and recipient.

To get access to these phones, law enforcement turns to NSO Group. Its software connects with the phone by spoofing legitimate WhatsApp communications. It exploits a bug in WhatsApp’s software to trick it into installing NSO software.

1

2

Install!

NSO Group

With the NSO software now running on the target’s phone, the company’s customers have a powerful spying tool that can read messages, take screenshots and download browser history and contact lists.

After identifying that journalists and activists have been targeted, on Oct. 29 Facebook sues NSO for hacking and notifies 1,400 targets that their phones may have been compromised. It doesn’t know the identity of most of these users.

3

4

Shortly after, the NSO software installed on these phones goes dark, either because the targets of investigations have reformatted their phones or discarded them.

5

Law enforcement learns of terror suspect using WhatsApp’s encrypted messaging, which scrambles the content of messages. These messages are only readable on the phones of the sender and recipient.

To get access to these phones, law enforcement turns to NSO Group. Its software connects with the phone by spoofing legitimate WhatsApp communications. It exploits a bug in WhatsApp’s software to trick it into installing NSO software.

1

2

Install!

NSO Group

With the NSO software now running on the target’s phone, the company’s customers have a powerful spying tool that can read messages, take screenshots and download browser history and contact lists.

After identifying that journalists and activists have been targeted, on Oct. 29 Facebook sues NSO group for hacking and notifies 1,400 targets that their phones may have been compromised. It doesn’t know the identity of most of these users.

3

4

Shortly after, the NSO software installed on these phones goes dark, either because the targets of investigations have reformatted their phones or discarded them.

5

Law enforcement learns of terror suspect using WhatsApp’s encrypted messaging, which scrambles the content of messages. These messages are only readable on the phones of the sender and recipient.

1

To get access to these phones, law enforcement turns to NSO Group. Its software connects with the phone by spoofing legitimate WhatsApp communications. It exploits a bug in WhatsApp’s software to trick it into installing NSO software.

2

Install!

NSO Group

With the NSO software now running on the target’s phone, the company’s customers have a powerful spying tool that can read messages, take screenshots and download browser history and contact lists.

3

After identifying that journalists and activists have been targeted, on Oct. 29 Facebook sues NSO for hacking and notifies 1,400 targets that their phones may have been compromised. It doesn’t know the identity of most of these users.

4

Shortly after, the NSO software installed on these phones goes dark, either because the targets of investigations have reformatted their phones or discarded them.

5

Sources: Western European security officials, Facebook, NSO Group

NSO told The Wall Street Journal that its technology “is only licensed, as a lawful solution, to government intelligence and law-enforcement agencies for the sole purpose of preventing and investigating terror and serious crime. As our technology is operated solely by the law enforcement or intelligence agencies themselves, NSO does not comment on related operational issues.”

After an investigation, Facebook said it linked servers and WhatsApp accounts used in the hack to NSO. It alleges in the lawsuit that the hacking was done to install NSO’s spyware, called Pegasus, on targets’ devices. NSO hasn’t responded to questions about whether it installed the spyware.

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

How much leeway should law enforcement be given to track suspected criminals? Join the conversation below.

NSO has faced criticism for selling its products to government agencies in the Middle East, Mexico and India, which Facebook and human-rights research group Citizen Lab, among others, allege used them to spy on dissidents, religious leaders, journalists and political opponents. Among the 1,400 WhatsApp users notified in October, more than 100 fell into these categories, Citizen Lab said. The group, which is based at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy, worked with Facebook on identifying these people.

NSO said most of its customers are democratic European governments that use its products in criminal and terror investigations. The company also maintains that it isn’t privy to the identities of people surveilled by governments using its technology. NSO says it investigates any misuse of its technology it learns of, such as surveillance outside of a criminal investigation. It says it doesn’t allow mass surveillance and that Israel’s defense ministry must approve any foreign sale of its products.

Government agencies in many Western European countries employ several companies at once, layering the surveillance technology to increase the variety of devices that can be hacked and to have backups if one technology fails or is rendered useless, one current and one former European security official said. In some cases, they said, NSO’s spyware was the best way to learn details of criminal plots.

Citizen Lab has issued reports for several years linking NSO’s spyware to governments with a history of human-rights abuses, and said that record should put NSO out of the running for government contracts from Western agencies, said

Ronald Deibert,

Citizen Lab’s director. “What we have been trying to do with our research is to raise alarm bells.”

WhatsApp, which notified the Justice Department about the hacking in May, called in October for a moratorium on the use of tools such as NSO’s, saying they need legal oversight to prevent their misuse.

A Justice Department spokesman declined to comment.

Photo:

Daniella Cheslow/Associated Press

WhatsApp isn’t the only tech entity targeted by NSO’s technology: In 2016, Apple also released a security patch to close a vulnerability that allowed iPhones to be hacked.

On the day WhatsApp sent its alert, the official overseeing the terror investigation in Western Europe said, he was stuck in traffic on his way to work when a call came in from Israel. “Have you seen the news? We’ve got a problem,” he said he was told. WhatsApp was notifying suspects whom his team was tracking that their phones had been hacked. “No, that can’t be right. Why would they do that?” the official said he asked his contact, thinking it a joke.

The most immediate concern was a suspected terrorist investigators linked to Islamic State. They had received a tip he was part of a group plotting an attack around Christmas. Once they saw the suspect’s phone receive WhatsApp’s alert, the phone went dark, the official said. The sleuths soon lost access to the suspect’s messages, the official said, indicating he had discarded or disabled the phone.

“We only had that one phone,” the official said. “We put all our efforts into using this product to see what he was doing, which mosque he was going to, who was talking to him, whether the group was spread in neighboring countries.”

The interception of data from the suspect’s phone had gone on for just a few days before WhatsApp alerted the target. This meant the monitoring period had been too short to glean details of the suspected plot, the official said. The suspect had left his phone at home when he went out and was sending only brief messages, making investigators’ work more difficult.

Then WhatsApp sent its message: “An advanced cyber actor exploited our video calling to install malware on user devices. There’s a possibility this phone number was impacted.”

“WhatsApp killed the operation,” the official said. The terror suspect is still under traditional surveillance. But human resources are spread thin, the official said, especially around the winter holidays, which in Europe extend into early January and are a time when terrorists have staged attacks on the continent. “He’s not the only suspect we have to follow.”

The European official said NSO spyware had enabled his team to learn details of a separate gang of violent bank robbers and weapons traffickers and have police arrest them as they were about to commit a crime. In that case, they got lucky, the official said: “One gang member’s phone we had infiltrated was already in police custody when the WhatsApp message landed.”

The official said counterparts in other Western European countries told him more than 10 of their investigations may have been compromised by the WhatsApp alert. “I talked about it with my colleagues,” the official said. “They also couldn’t believe this was happening. It affected them more because they used this WhatsApp tool more than we did.” The former security official, from a different nation in Western Europe, said several countries there rely on NSO spyware in counterterrorism investigations.

Facebook and other U.S. technology companies often inform users when a government agency is legally requesting their data, unless prohibited by law or if the company believes there are “exceptional circumstances, such as child-exploitation cases,” Facebook says on its website.

NSO’s technology bypasses the traditional legal request process, however, according to Facebook, Citizen Lab and others.

“From the company’s perspective, the data has been stolen and some of the companies obligate themselves in their terms of service to notify their customers when a theft of data occurs,” said

Gregory Nojeim,

senior counsel with the Center for Democracy and Technology, a nonprofit privacy-advocacy organization.

In a move highlighting the complex legal landscape tech companies and law enforcement must navigate in Europe, new European Union rules kicking in by the end of 2020 will oblige telecommunications companies, including Facebook, Google and Skype, to warn customers about security threats precisely the way WhatsApp notified its users in October.

The European official said his own unit is so secretive that senior security and government officials in his own country don’t know about the methods and tools they deploy. When evidence gathered by his unit is used in court, efforts are made to hide the true source of the evidence.

European governments started purchasing hacking tools after a string of terrorist attacks in 2015 exposed the intelligence gaps created in the era of smartphones and encrypted messaging apps.

Gilles de Kerchove,

the European Union’s counterterrorism coordinator, says encryption shouldn’t allow criminals to be “less accountable online than in real life.”

“We have to find a balance between protecting privacy and investigating crime,” he said.

Write to Valentina Pop at [email protected] and Robert McMillan at [email protected]

Copyright ©2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8